Jill Goldberg, a former

Women in Black member and an experienced Jewish peace activist, is a little confused. We believe in helping people, so we will try to help her understand two or three things. In opposition to the

call to boycott the Batsheva dance company, Goldberg reviews the performance and writes:

Watching the superlative talent that went into Deca Dance, I was transfixed; how could participating in such imaginative, such beautiful, such clever art not be edifying? Deca Dance was such a tremendous offering that I feel certain that such a performance has the ability to reach people in a way that transcends the harsh reality of life in the quagmire that is the Middle East. If art is the triumph of imagination over crude reality, then Deca Dance is the proverbial victor, vanquishing the ordinary with the power of creativity as its only weapon. At the risk of sounding naïve and overly idealistic, I have to wonder: if the small group of protesters outside had snuck in and watched Naharin’s choreography, would they be moved out of the rigidity of rhetoric and into the relative softness of dialogue? Would they see something in the work of these immensely talented Israelis that showed them that they too are human with the same longings for peace and security and the same fears as their Palestinian brethren? (Plank Magazine)

Goldberg seems to think that the call to boycott Batsheva is rooted in a negative aesthetic judgment on its art. Absolutely not. Batsheva is a leading dance company. Oded Naharin is a talented choreographer. The call to boycott Bathsheva is a non-violent strategy in the struggle against Israeli apartheid that is rooted in a moral and political understanding of the context of Israel's artistic output. It is not

a aesthetic judgment.

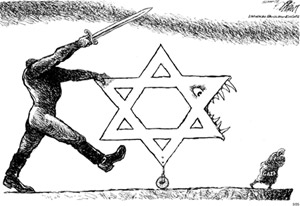

If one of the tenets of fundamentalism is the belief the sacred text was written directly (or at least dictated) by God, there is a widespread fundamentalist philistinism today that sees art in exactly these terms, not as work, not as a human product, but as direct revelation, the true religion of the high minded. It is a form of philistinism that loves art the way flag waving Americans love their country. An element of this philistinism is to divide culture between the two mutually exclusive categories of art (revelation, prophecy) and propaganda (imposture). Either, for example,

Churchill's play is art, or it is worthless agitprop, propaganda. The revealed Truth that the high-minded philistines discover through art is always the One, humanist and universally shared--as Goldberg puts it--"reflection of what it means to be a..human being", and therefore anything political or divisive, or indeed any contextual meaning that is less total than that humanist revelation, is an intrusion of the profane. That this is absurd requires only a minimal knowledge of the history of art. Is the Sistine Chapel, painted by the greatest renaissance artists, any less of a work of art for being a work of blatant political propaganda? Batsheva's performance's artistic merit does not preclude it being also propaganda work for Israel and thereby facilitating the murder and continued ethnic cleansing of Palestinians.

The work of art is always done in the service of two masters at least. One master is, one could say, revelation, recalling us to our senses by addressing our sentient capacity, jolting us, making us feel, making us aware of our conscious being. The second master is the one who buys the artist's lunch (a person, an institution, an audience, aa community, a system, etc.). Sometimes, when the artist also wants to say something through art as an engaged agent, art has a third master as well, the artist's conscience. That third master is not necessary like the first two. Art can and often does exist without it. But there can be no art without an invitation to experience, and there can be no art without the social relations that sustain the artist. Art can serve as propaganda in a variety of ways. It can speak directly for the second master, as the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel do. It can speak directly for the third master, as Diego Rivera's "Man at a Crossroads" did. But art can also serve as propaganda indirectly, whether by naturalizing, falsifying, glossing over, reconciling, justifying or symbolically resolving conflict, or simply by being vague, as the art of Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko,

appreciated and promoted by U.S. capital in the Cold War because it didn't speak of anything. Finally, art can serve as propaganda by externally associating the revelation of art with either a political cause or the patron and paymaster. This at least is certainly the case with Batsheva, financed and promoted by the Israeli government as a "cultural ambassador" for Israel, thus helping to advance the goals of campaigns such as "

Rebrand Israel," which seeks to improve Israel's image (and thereby facilitate Israel's ethnic cleansing of Palestinians), by among other things

using artists to represent Israel.

Being moved and "edified" by a work of art is not the be-all of appropriate responses. One can be awed by the technical prowess and impressed by the expression of energy and purpose of Leni Riefenstahl's "Triumph of the Will," yet condemn it as a work of willing service to one of the vilest movements in world history. One can appreciate the exacting animation of David Polonsky and Yoni Goodman in "Waltz with Bashir" while

fuming about the way that film whitewashes and embellishes Israeli responsibility for a minimum of 18,000 deaths in the 1982 Lebanon war and symbolically erases Palestinians from Israel's collective memory. Artists make choices. They make artistic choices within the work of art itself as well as professional choices within a social and political context in which they create their art, present it and make a living out of it. All these choices have moral and political implications to which indifference in the name of high-minded humanity is a special kind of genteel philistinism. Goldberg's review has eyes only for humanist exultation. The pieces evoked for her "the sacred and the transcendent power of prayer," or "the realm of human sexuality," or "a lofty and visionary" imagination. I don't know if that is because the performance does not lend itself easily to finer grained interpretations or because Goldberg is unable to respond to art in any other way than as a religious service for unbelievers. Her only contextualized reaction was to a piece that reminded her of her cousins who served in the Israeli army, and "all of them born and bred, like Naharin, on a kibbutz, all of them hungry for peace in the region." It is amazing that the only political reading of the performance that Goldberg recognizes is exactly the message of Israeli propaganda, that Israelis suffer from the wars they wage and yet yearn for peace,

shooting and crying. It is even more amazing that her reaction reproduces a set theme of Israeli racism against non-European Jews, representing the racially exclusive kibbutzim as the home of Israel's best and most conscientious. She could hardly have come up with a clearer argument in favor of the boycott. Goldberg hopes, "naively," that the protesters outside see the performance and recognize the humanity of Israelis. But was that humanity ever in doubt? Isn't the humanity of Israelis and the bestiality of Palestinians/Arabs/Muslims the fundamental ideological matrix through which the conflict is represented in the U.S., in the press, TV, Congress, etc? How about humanizing Palestinians? How about asking why nothing in Naharin's work evoked for her a meaning that might challenge the U.S. audience's understanding of the country from which Batsheva comes?

Goldberg praises Barsheva for reaching "people in a way that transcends the harsh reality of life in the quagmire that is the Middle East." But who are those reached? Whose harsh reality is being transcended and by whom? What does it mean, what kind of artistic intervention it is, to help people who suffer little of that reality "transcend" it in their minds? Can Palestinians "transcend" the checkpoints with the help of Naharin's powerful images? Can his deeply moving art console the mother of

ten-year-old Mahmoud Ghazal? Or does it make it easier for someone who never heard of Mahmoud Ghazal to "transcend" that irrevocable absence she is not and will never be aware of? And if the latter, is that to be praised or rather challenged?

Goldberg would have like the work of art to help the protesters "be moved out of the rigidity of rhetoric and into the relative softness of dialogue." This is not a very intelligent comment: real dialogue is hard; only dialogue with the mirror is soft. And rhetoric can be either soft or harsh depending on how one wants to be be received. But the demand for boycott

is in fact a form of dialogue, real, truthful and honest dialogue. It is dialogue with the audience of the Batsheva dance company about how to understand their own relation to what is taking place in the Middle East. It is also a dialogue with Naharin and his dancers. Naharin's public comments suggest an understanding of his role as an artist is limited and self-flattering. He commented on the boycott:

The boycott is just preventing something that is good....I think artists belong to a group of people who don't represent the ugly side of Israel. They represent people who have compassion and who are willing to give up a lot for peace. And artists everywhere usually represent something missing from politics: the search for new solutions. (straight.com)

Shouldn't artists in fact represent the "ugly side of Israel"? Shouldn't Naharin be aware that the state of Israel uses artists as agents of beautifying ethnic cleansing? For example, after Jaffa was destroyed in 1948, the Tel-Aviv municipality gave Israeli artists and writers subsidized, privileged

homes and studios in the Disnified "Old Jaffa," using glamor and art's prestige to legitimize the ethnic cleansing of 1948, and using the gifting of stolen Palestinian property as a way to buy the silence of the artists. Isn't that silence something one would describe as "ugly"? Shouldn't Naharin recognize that his role as "cultural ambassador" makes him particularly complicit, over and above his citizenship, in the continuing ethnic cleansing of Palestinians?

“We will send well-known novelists and writers overseas, theater companies, exhibits,” said Arye Mekel, the ministry’s deputy director general for cultural affairs. “This way you show Israel’s prettier face, so we are not thought of purely in the context of war.” (NY Times)

When Naharin assures us that artists "are willing to give up a lot for peace," isn't it fair that Palestinians cash this promise and demand to see what exactly Naharin is willing to give up as an artist?

Is he for example ready to do what Paul Ben Itzak, editor of Dancer Insider, would like to hear him do? Challenge his audience before every performance with words such as:

We are now spectators of the latest -- and perhaps penultimate -- chapter of the 60-year-old conflict between Israel and the Palestinian people. About the complexities of this tragic conflict billions of words have been pronounced, defending one side or the other.

Today, in (the) face of the Israeli attacks on Gaza, the essential calculation, which was always covertly there, behind this conflict, has been blatantly revealed. The death of one Israeli victim justifies the killing of a hundred Palestinians. One Israeli life is worth a hundred Palestinian lives.

This is what the Israeli State and the world media more or less -- with marginal questioning -- mindlessly repeat. And this claim, which has accompanied and justified the longest Occupation of foreign territories in 20th century European history, is viscerally racist. That the Jewish people should accept this, that the world should concur, that the Palestinians should submit to it -- is one of history's ironic jokes. There's no laughter anywhere. We can, however, refute it, more and more vocally. (Dancer Insider)

Is Naharin ready to make Batsheva officially take a "position calling for an end to the occupation, not to mention recognizing UN-sanctioned rights of the refugees or ending racial discrimination against the state's 'non-Jewish' citizens (the remaining indigenous population)." as Omar Barghouti

demands?

Is he ready to produce and tour with dance pieces that the New York Times reviewers might perhaps deascribe as "anti-israeli propaganda" because they would challenge the audience's understading of the Israel and the conflict?

None of it would be easy for a group paid with the money of the Israeli government. Perhaps Naharin would lose his livelihood if he tried. Isn't it a risk worth taking? Artists have been arrested, jailed, beaten and murdered for standing up to lesser inequities. Is talent a license to collaborate? Shouldn't artists take some risks before they seek to express "the triumph of imagination over crude reality"? Perhaps Naharin would fail. But is it unfair to insist that he wrestle with the institutions that fund him, use his prestige and recognition and negotiate perhaps a way to work that would represent, not just the state that is, but also the state that would be, once this racist regime is defeated? How come there are no Palestinian dancers in his "Israeli" dance company when over 20% of Israeli citizens are Palestinians? How come there are no conscientious objectors who refuse to serve in the army in this dance company of artists ready to "give a lot for peace"? Surely they can do better than that.

Naharin and his dancers can choose the masters they serve. It is up to them how to respond. It is their political awareness or lack thereof. Their professional ethics or lack thereof. Their conscience or lack thereof. Their character or lack thereof. But to impose these demands through a strategy of boyoctt, divestment and sanctions IS dialogue. Is it dialogue that respects art as human endeavor, as a democratic and equal exchange, not as an opportunity for sentimental and costless communion with the tragic (primarily for others) spirit of humanity. It is not the dialogue favored by the doyens of the peace industry, pointless, decade-long chatter with no consequences. It is dialogue that demands answers, responsibility, and proof of delivery from those claiming to represent enlightenment and speak for peace. What Jill Goldberg recommends instead is for Israelis to stick to their internal monologue, shooting and crying about it; and for Palestinians to stay silent and appreciative. These days are over.

a aesthetic judgment.

a aesthetic judgment.